Kiwa

Japanese sense of framing : non-separation of inside and outside

Kiwa is a most important concept in Japan, which means much more than the physical edge of things. Kiwadatsu—the verb, “to stand out”—is comprised of kiwa and tatsu (to stand), and is a foremost quality sought in Japanese design. In the fiery accents of Jomon pottery; the layered combination of ceremonial robes; the hemmings of tatami mats, fusuma sliding doors, and byobu screens; and the collar under kimono—in kiwa dwells the kiwami (acme) of design.

This sensibility around framing differs from Western framing in that it connects inside and outside without a hard separation. In housing structures it can be found in the shape of hedges, eaves and engawa verandas. The spatial boundaries, where the home extends out into the world, have helped shape Japan’s sense of community. Furthermore, as the “slowly paling mountain rim” (yama-giwa [=yama-kiwa]) is celebrated in the line, “In spring, it is dawn” of The Pillow Book, the Japanese have long found beauty in the kiwa of changing times—the critical last moment (seto-giwa), the moment before parting (sarigiwa), or separation (wakare-giwa).

Analogy in Polytheism

Daily life in Japan offers a veritable thesaurus of terms pertaining to kiwa. These include words such as kiwameru (to master), kiwadoi (too close, risky), kiwami (acme), kiwamono (peculiar/odd things), kiwakiwa (borderline), setogiwa(the eleventh hour), magiwa (just before), haegiwa (hairline), namiuchigiwa (water’s edge), madogiwa (window sill), sumi (interior corner), kado (exterior corner), heri (hem), fuchi (rim), hashi (tip), kire (fragment), kagiri (limit), sumikko (corner), bubun (parts), ma (pause/space), and so on. Why such love for edges and boundaries?

Being a land of countless deities, the Japanese chose rythmic succession of word and image as well as resonance of meaning, over the integrity and perfection of logic. The culture of za (guilds), as seen in renga linked verses and the chanoyu tea ceremony, was made possible through the association of analogous ideas and through creative collaboration. Something takes hold of the subtle workings of the human heart when images deriving from similar events or phenomena are superimposed onto each other–a tremor occurs in the interface, or kiwa, between adjacent entities.

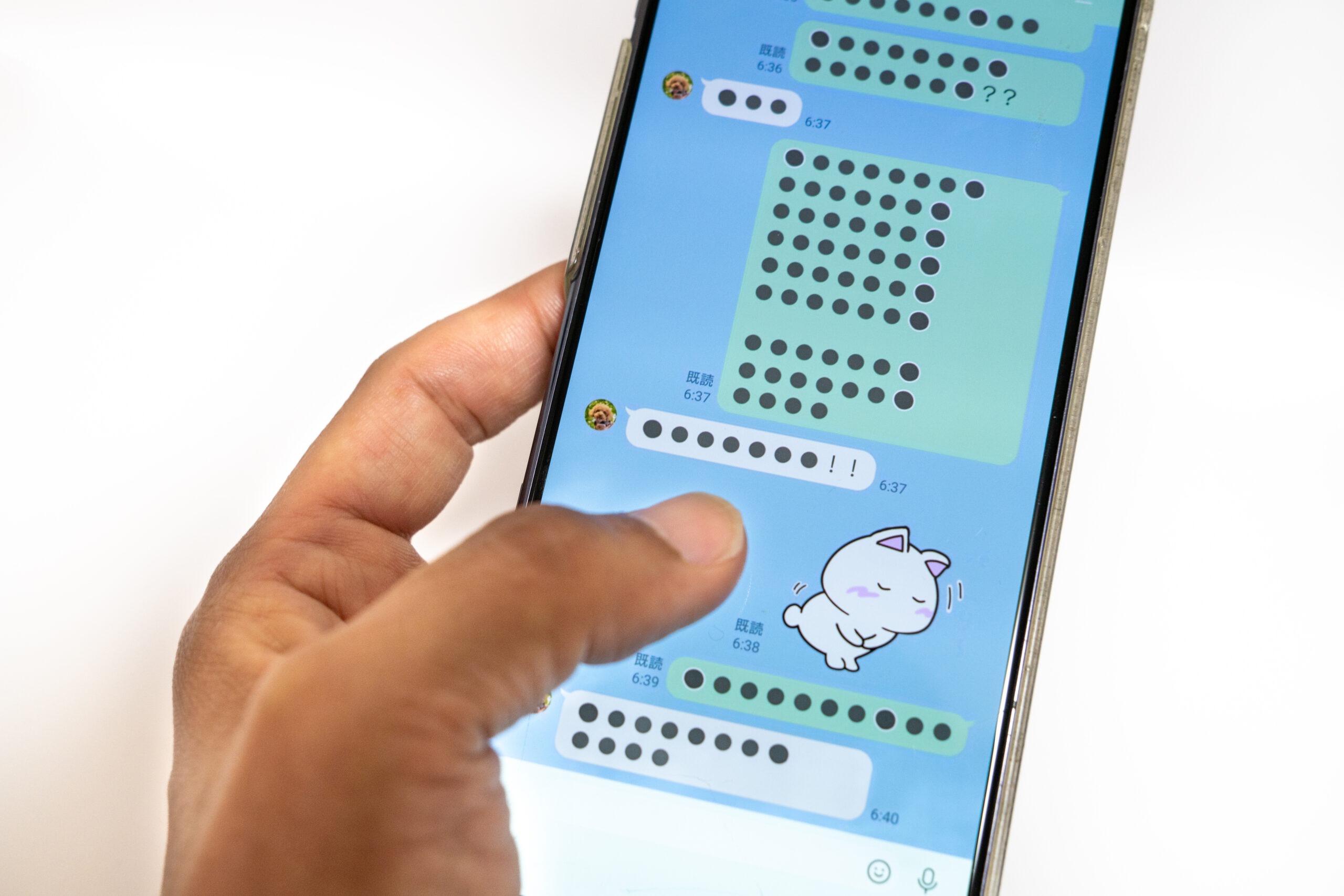

Today, we can witness this sense of kiwa alive in the delicate adornings of nail art; in LINE stickers, which replace phatic responses for smoother communication; and in the clever wrapping design of rice balls in convenience stores.