Shu(Heed)・Ha(Break)・Ri(Depart)

The concept of kata is a crucial key to understanding the transmission of knowledge within Japanese culture. Kata literally translates as “mold” or “cast,” but a broader definition of the word would include such English terms as form, frame, structure, type, and model. Some kata are still and constant, like the paper stencils for dying fabric. Others are more fluid in nature, existing in motion, like the kata of dance, sumo, and ceremonial etiquette, which require bodily experience and knowledge. Shu-ha-ri is the Japanese model for ensuring the transmission of such kata.

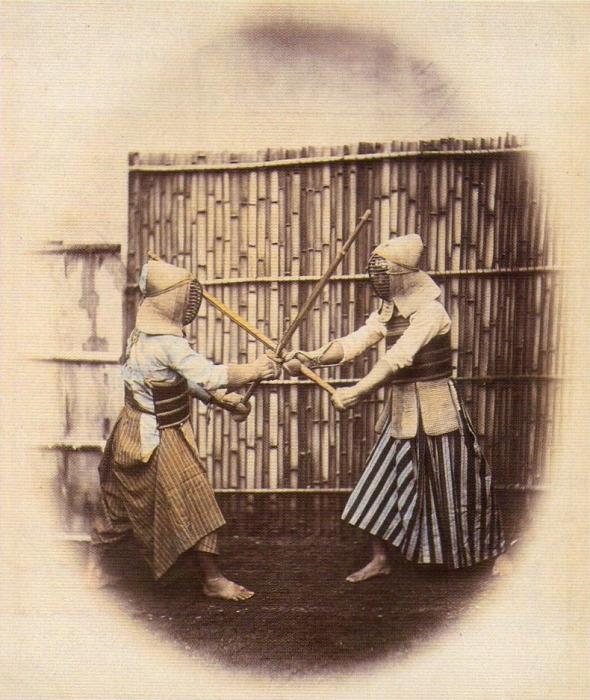

This learning model originates from the jo-ha-kyu (open-break-rush) structure of Noh drama, which was mixed with and incorporated into other disciplines, such as Zen Buddhism, renga (linked-poem) parries, and the Way of Tea. Eventually, this basic dramatic structure was recognized as an effective methodology for establishing the feel or mood of certain spaces or communities. Under the additional influence of budo (martial arts), with their esoteric tendencies, shu-ha-ri emerged―a method of handing down knowledge that cannot be put into words.

Shu means to heed or to guard. It is the beginning stage, in which traditional kata are hammered into the apprentice. Total adherence to kata is required. The second stage, ha (literally, to tear apart or to break away), is where students learn to use kata in action, finding new applications of the traditional forms, which requires a sense of creativity and sometimes the courage to break the mold. Ri (to depart) is the final stage of mastery, where the kata flows naturally and freely from within. In this stage, the practitioner is no longer bound by the detailed rules of any specific discipline and can apply his or her knowledge across all situations.

Kawakami Fuhaku, founder of the Edosenke school of Tea, has put it this way: “The teacher must teach shu to the student. Students who devote themselves to the learning of shu will on their own find the way to ha, the breakthrough. Ri is to put together the two and depart from them, while still adhering to their principles.” Kawakami’s words explain the basic learning process used by artists and technocrats alike in Japan.

Today, as traditional pottery skills are applied to industrial ceramic technology and mirror-polishing skills to the production of satellite antennas, traditional kata continue to give birth to new kata across many industries. In this way, the workings of kata—based on transmission of knowledge from master to disciple—are not limited to the arts. In fact, kata underlie the majority of modern Japan’s skills and technologies.

Learning and instruction manuals may indeed be effective and applicable to all. But Japan’s original learning process, as represented by shu-ha-ri, was always based on creativity fostered through mentorship, based on the mutual and simultaneous act of bridge-making by teacher and learner. Art, school, shop, factory—no matter what the environment, it is this rigorous learning process that has activated Japan’s creativity.