Shin(truth)・Gyo(way)・So(grass)

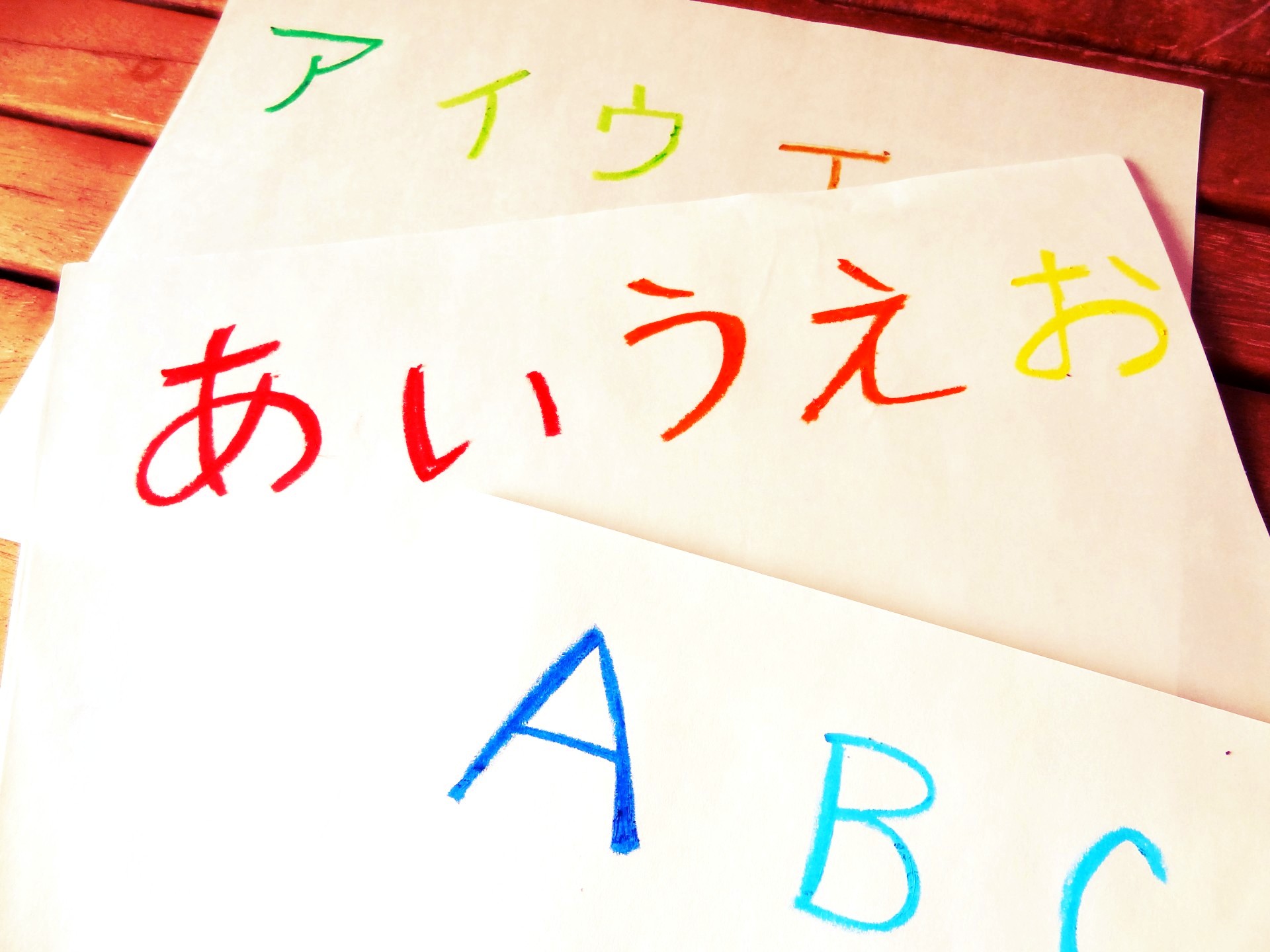

Shin-gyo-so is a trinity of concepts, crucial to understanding the cultural modes and styles of Japan. The characters— which mean “true,” “going,” and “grass”-are used to represent formal, semi-formal, and informal, and stem from the three basic styles of calligraphic brush techniques.

Shin is orthodox formal script, used mainly to communicate official information. So is a free-flowing cursive script that, while maintaining core structures of its roots, allows ample room for the sensibilities and artistic interpretations of the writer. Gyo, then, is semi-cursive script somewhere in between the other two—in which we can witness the process of mutation from formal to casual.

The people of medieval Japan considered anything from the neighboring continent as authentic. Consequently, the world shin was used to describe the objects and styles of China. The Tea Ceremony, for example, was initially based on the respected Chinese format and only Chinese utensils were considered proper. Eventually, however, there was a move away from worshipping the China brand.

This movement accelerated with the appearance of Murata Shuko―a Tea practitioner, who frequented the cultural salon of Zen master Ikkyu. Shuko saw that it was possible to blur the line between Chinese and Japanese to create a fusion of styles, and thus started the Japanese arts on a new journey of discovery and evolution that would lead to the spirit of wabi.

Wabi—in its most literal and original sense—is an “apology” for not having a proper and formal shin environment to welcome guests. The Tea masters, conversely, found virtue m this very spirit. Using humble grass hues and the simplest utensils, they pursued this sense of humble beauty as the so style of Tea. The style was further elevated and perfected by Sen no Rikyu, and later enhanced by inspired innovators such as Furuta Oribe and Kobori Enshu, who injected bold creativity to the art and applied the same thinking to gardening, cuisine, and other aspects of general culture.

From the arts to technology and throughout daily life, the concept of shin-gyo-so can be found everywhere. The Japanese continue to create their own gyo and so styles out of the shin or “global standard,” and they enjoy the act of picking from among the three styles that which is most appropriate for whatever situation is at hand. In fact, it is this love for frequent mode-shifting that brings a unique sense of depth to Japanese culture.