Sabi(Rustic beauty)

Fresh green glaze on a distorted tea cup. Furuta Oribe, a 16th century military general and student of grand tea master Sen no Rikyu, pursued beauty in things that were “blemished” and “insufficient.” True beauty was not to be found in perfection, according to Oribe. A piece of art did not even need to appear finished. His interest rather, laid in the intrigue of the mange, and he thus brought new meaning to the concept of beauty in the world of tea, freeing it from the stoicism of Rikyu’s wabi.

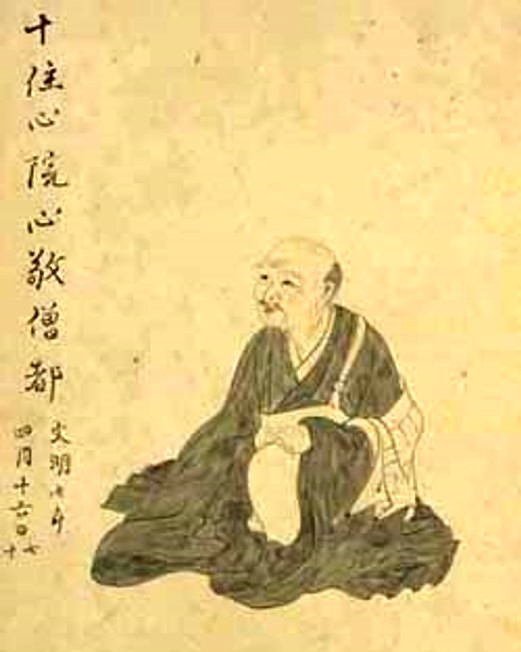

Next came Kobori Enshu, who incorporated the concept of sabi (withered loneliness)—highly valued in waka and haiku poetry—into the discipline of tea. Adding to it a touch of extravagance, he came up with his own version, which he called kirei sabi (brilliant sabi).

The playful innovation and transformation of aesthetic ideas, like those of wabi and sabi, was called susabi (from susabu, “to storm”) or suki (related to, suku, as in “to like”, but originally meaning “to screen”). The same creative tendencies creativity have been largely inherited by modern pop artists in today’s Japan.